“Ah, this is obviously some strange usage of the word ‘safe’ that I wasn’t previously aware of.” —Douglas Adams

There are people who don’t like various aspects of our business. There are those opposed to science in general. Then there is a rather larger group who are against chemicals. Never mind all that carbon, nitrogen and oxygen in their bodies, they want “chemical-free” products. There is a significant group who take issue with the safety of many chemicals used in personal care products, and especially some specific components such as parabens, sulfates and phthalates.

There is a vocal group of consumers who are against the use of fragrances. Lest you think they are all unscientific fanatics, remember that there are a lot of cosmetics that boast of being “fragrance free.” It is a complicated and emotional situation, with no simple solution. We certainly must be aware of the varied aspersions cast upon us. We need to make the safest possible products, and then it is critical to communicate that fact clearly to our customers and the general public.

Since you are reading this, we at least know that the Large Hadron Collider did not create a black hole and swallow the Earth, but suspicion of science continues. In 2001, the American Chemical Council started a “good chemistry” campaign placing emphasis on “chemistry” rather than “chemicals.” Dow Chemical launched its “Human Element” (Hu) campaign in 2006 to promote the benefits of chemistry. A key feature of Dow’s campaign was the insertion of Hu into the periodic table. The rise of green chemistry is certainly a positive trend, but it may be too technical in its essential nature to influence the attitudes of the general public.

A recent blast at our industry is Stacy Malkan’s book, Not Just a Pretty Face: The Ugly Side of the Beauty Industry.1 While most of it is not pleasant reading, it would be foolish to not consider some of the positive ideas it contains. If we jump to chapters 10 and 11, Malkan offers some inspiring ideas for future product development and brings us up to date with the activities of Horst Rechelbacher, while introducing the benefits of biomimicry.

Rechelbacher founded Aveda and sold it to Lauder in 1995 for enough money to be able to follow his dreams. He is a passionate advocate of organics, and believes that anything put on the body should be safe enough to eat. He created Intelligent Nutrients, his recently launched brand, more to show how his ideal products could be made rather than to recreate the commercial success of Aveda. He is extending the possibilities of organic formulations by making no compromises in the pursuit of new functional organic ingredients, however time-consuming and costly the quest may be.

Janine Benyus is a founding figure of biomimicry, expounded in her seminal Mimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature.2 The basic premise is that nature has devoted 33.5 billion years of trial-and-error to solving a multitude of problems, and the best ideas resulting from that process can be applied to our problems. Benyus has a 23-minute video lecture online, titled “12 Sustainable Ideas from Nature;” those ideas are shown in Figure 1. (Her Web site offers visual and audio of where she finds inspiration.3) Some of these concepts are directly applicable to our industry. Leaves usually don’t get dirty—nature, in general, is clean—and this helps shed light on cleaning without detergents. Leaves often have tiny hair-like structures on their surface to keep dirt from adhering. A product based on the lotus leaf—Lotusan, created by Klaudius Kurtz, a house painter in Germany—does just that. Further, using biomimicry, an antibacterial film was developed by Biosignal, an Australian company. The company studied a seaweed in which natural compounds prevent bacteria from gathering. A film was created that interfered with the signals used by microbes to communicate with one another, which prevents bacteria from colonizing. The film thus prevents infection without creating superstrains of harmful bacteria.

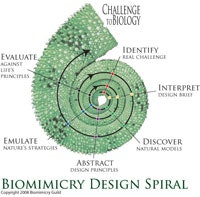

There are several organizations promoting biomimicry. The Biomimicry Institute offers a design portal, described as “a digital library of nature’s solutions organized by function that is both a cross-pollinating tool and a collaboration forum.”4 Also on its site, the Biomimicry Design Spiral was created by Carl Hastrich to teach biomimicry principles in a visually understandable form (Figure 2).

Finally, a feature in The New York Times on WALA’s Dr Hauschka5 noted the brand’s basis on the anthroposophic teachings of Rudolf Steiner, who encouraged biodynamic agriculture. Dr Hauschka, in fact, shuns organic certification in the U.S., feeling its own methods are much stricter. The garden in which its materials are sourced is beyond organic; visitors, for example, cannot use cell phones in order to “avoid disturbing the harmony of nature.” Founded by Rudolf Hauschka in 1935 to develop natural remedies, the biodynamic garden was planted in 1955. The crops are harvested by hand, and ingredients are extracted using water, emphatically not alcohol or other solvents.

These ideals—along with some of the brand’s other sourcing initiatives—too may hold lessons for wider industry application. And a book like Malkan’s can serve to jolt us out of complacency—even as we refute certain aspects.

Our industry may not be perfect, but many companies have embraced natural products, organics and green chemistry. We have placed a high value on safety, truth in labeling, efficacy and global harmonization. Easily 95% of our consumers are very satisfied with our products. Let us take pride in our achievements and use our critics to inspire us when they have constructive suggestions.

References

- Malkan, Stacy, Not Just a Pretty Face: The Ugly Side of the Beauty Industry, New Society Publishers: British Columbia, Canada (2007)

- Benyus, Janine M., Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature, Harper: New York (2002)

- www.ted.com/index.php/talks/janine_benyus_shares_nature_s_designs.html

- www.biomimicryinstitute.org

- Landler, Mark, “Garden Is a Seedbed For Green Cosmetics,” The New York Times, Jun 28, 2008

Steve Herman is the technical sales director for J&E Sozio. He has been an adjunct professor in the Fairleigh Dickinson University Masters in Cosmetic Science program since 1993, teaching Cosmetic Formulation Lab and Perfumery. His book, Fragrance Applications: A Survival Guide, was published by Allured Publishing Corp., Carol Stream, IL, in 2001. He has served as chairman of the SCC’s New York chapter, and was elected to fellow status in 2002.